Abstract

THE CLIMATE OF SOUTHERN PORTUGAL DURING THE 18 th CENTURY

RECONSTRUCTION BASED ON DESCRIPTIVE AND INSTRUMENTAL SOURCES

Historical Climatology has not been a privileged area of study in Portugal. Besides the organisation of the meteorological observations with the use of instruments prior to the foundation of the Infante D. Luis Observatory carried out by Ferreira in the nineteen forties, the first studies emerged only in the last decade of the twentieth century and were almost exclusively developed within the European project ADVICE. This report presents no more than the result of a survey of the reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall rhythms in the 18th century in Portugal. Hence, it should not be regarded as other than an initial contribution to the knowledge of Southern Portugal’s climate.

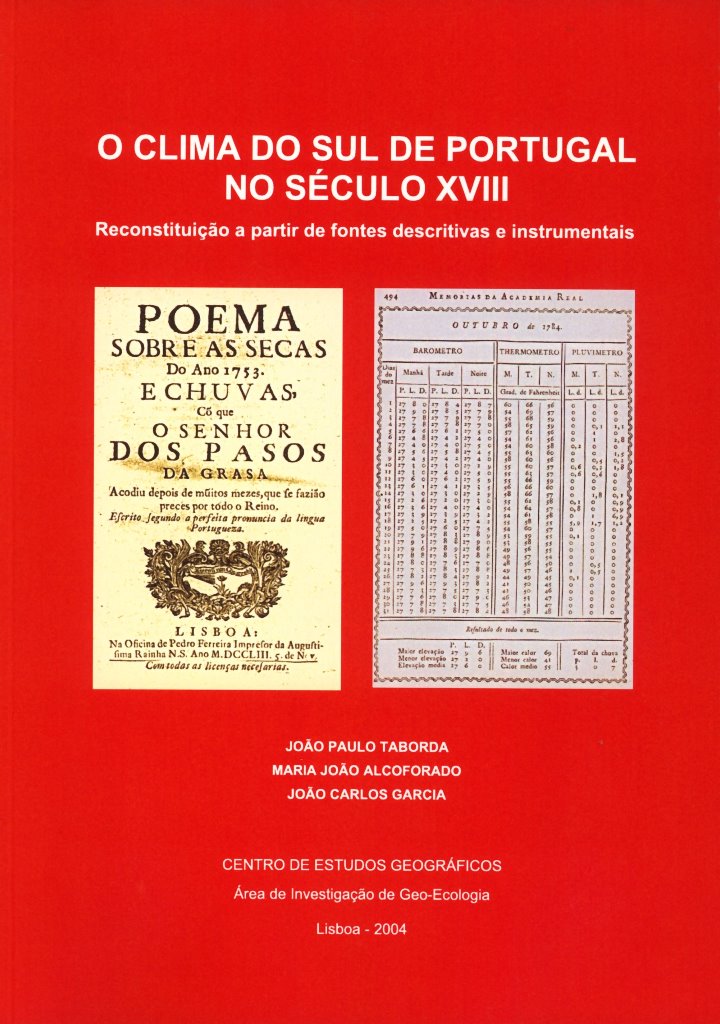

Meteorological observations with the use of instruments began in Portugal only in the latter decades of the 18th century. This study is to a great extent based in descriptive documental sources. The research carried out revealed an extraordinary wealth of meteorological and climatic information, dispersed among the Portuguese historical documental sources, of which some were institutional, some private, as well as the press. News that was not explicitly within the object of investigation was rarely used. In other words, news that did not allude directly and undeniably to weather conditions, to atmosphere conditions, and to meteorological elements was not used. The application of this type of information reveals some problems relating to the subjectivity of the accounts, particularly those referring to thermal conditions, due to the sporadic and non-systematic character of the records. Several procedures were used in order to evaluate the quality of the information. These included biographical examinations for every private record, diversification and intersection of sources as well as semantic analysis and comparison of qualitative information with the instrumental data.

It is generally the extreme climatic situations (prolonged droughts, violent rainfall, long-lasting rainfall periods, extreme heat or tierce snowfall) that were mentioned in the several types of sources used. The biggest volume and reliability of news relating to rainfall phenomena allowed for its “semi-quantification” and transformation into a monthly index divided between -1 (“dry” month) and +1 (“rainy” month) and in which the value 0 (“normal” month) was attributed every time information was missing or the news indicated normal conditions. Considering that the records were based on extreme situations with socio-economic impact, the indices are interpreted as a measurement for the behaviour of extreme phenomena (intense and prolonged rainfall or droughts), rather than for the average precipitation.

Although more sparse, the information relating to temperature allow for some considerations.

The two first decades of 18th century were particularly cold when compared with the others. Between 1720 and 1799, not only did the references to “cold” diminish, they were also confined to the winter and spring.

After the study of some heat waves that occurred in spring, particularly in March (e.g. 1734 and 1781), one seems to reach the conclusion that, in conformity with the present time, they are related to the positive phase of the NAO index. Accordingly, a great part of western and central Europe registers positive temperature anomalies.

The 1708/1709, 1739/1740 and 1788/1789 winters show that the cold temperature crisis in the European continent, and specifically in mainland Portugal, may be related to different patterns at a large index of the pressure at sea level. However, in the past as in the present, these cold waves are invariably related to blocking situations of the western circulation and with the advection of North, Northeast and East cold air, associated to the latitudinal development of the Atlantic anticyclone (as happened in April 1713 and 1754) and to its position in more northern latitudes, namely on the British Isles (as happened in March 1700 and January 1740). It is also associated to an occidental extension of the continental anticyclone, sometimes connected to the Atlantic anticyclone; such is the case of January 1714.

The NAO index for the months with information regarding cold waves in Portugal always presents negative values. Furthermore, it seems to be greatly related to a pattern of pressure field at sea level characterised by the presence of an anticyclonic centre located on the British Isles associated to a low pressure centre over the central Mediterranean. March 1700 exemplifies that situation (NAO index = -1.35), January 1740 (-3.36), March 1754 (-2.00) and December 1788 (-3.5). The atmospheric circulation at high altitude in those months was probably characterised by the presence of an anticyclonic ridge over the Atlantic rim of Europe and by a valley immediately to the East, with a Southwest-Northeast axis.

The precipitation in southern Portugal was very variable throughout the 18" century. The correlation coefficient indicates that the yearly variability of rain was mainly related to the one that occurred during the spring trimester (r=0.91) and secondly with the winter one (r=0.81).

In the early 18th century three periods stand out due to their extreme characteristics. The first period was characterised by the occurrence of persistent rain throughout an extensive period of time (winter of 1706/1707 – summer of 1709 only interrupted by the scarce precipitation of the summer and winter autumn of 1707). The second and third periods (winter of 1711/1712 and the period between the spring of 1714 and the autumn of 1715), were characterised by a distinct situation, that is, by a precipitation deficit, particularly prolonged in the last case.

Strong rainfall variability in the south of the country characterised the 30’s. The liturgical manifestations Pro Pluvia in three years (1734, 1737 and 1738) and Pro Serenitate in two (1732 and 1736) support that conclusion. In fact, that decade was one of the most important for those kind of liturgical ceremonies in southern Portugal. Two periods stand out as drought situations: firstly, the one between winter of 1733/1734 and the winter of 1734/1735; secondly, the one from February 1737 until February 1738. A period with precipitation excess occurred between those two periods (between the autumn of 1735 and the spring of 1736).

The most relevant situation in southern Portugal in the latter 18" century (period in which there were already some instrumental records) is the cycle of rainy years initiated in 1783, which must have been prolonged until the late 80’s / early 90’s. The unbalanced precipitation in the south of the country deduced after the Lisbon and Mafra instrumental observations and after the news in the descriptive documental sources, seems to be connected to the climatic disturbance that aftected some European regions during the 80’s. Other aspects that merit reference are, for instance, the strong concentration of precipitation in Lisbon and in Mafra that occurred in December. Regarding Mafra (1783-1787), the analysis of the wind direction leads to the conclusion that despite the fact that the main winds were from North, Northeast and Northwest, it was the winds from Southwest, South and Southeast that were related to around two thirds of Mafra’s precipitation during those years. The most intense precipitation was also associated with those wind directions, particularly the Southeast and South ones.

As demonstrated by several authors, the winter precipitation in the Iberian Peninsula in the past as in the present is correlated with the North Atlantic oscillation. Several simple regressions were made in order to evaluate the relation between the precipitation and the NAO index in the 18th century in southern Portugal. The r higher values were invariably obtained in spring (March-May). The volume and the quality of the information supporting this study are not consistent throughout the 18th century. For that reason, some regressions were also made for several periods. Attempts were made in order to verify when the relation between the NAO index and the precipitation in Southern Portugal was the strongest. The periods 1728-1764 and 1779-1799 achieved the best results, if one neglects the first fifteen years of the century, that were periods with the longest array of news and, simultaneously, more reliable information, which may explain the higher r values including in the winter.

In conclusion it is relevant to emphasize again that this study does not allow for more than a fragmented understanding of the climatic variability, particularly the precipitation, in the 18th century in southern Portugal. In order to increase and deepen the knowledge of the past climate in Portugal it is extremely important to continue the research and the systematisation of the records and historic documental sources. That work should be extended to the investigation in libraries and archives around the country. Furthermore, the study and the systematic analysis should be undertaken under a joint strategy and an interdisciplinary perspective.

The titles of figures and tables are translated into English on p. 205 and 211.